First Sunday in Lent, year A (preached 3/5/17)

first reading: Genesis 2:15-17, 3:1-7

Psalm 32

second reading: Romans 5:12-19

Matthew 4:1-11

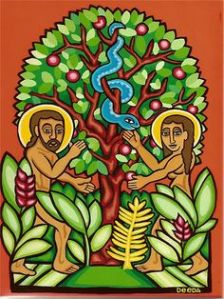

I’ve never liked the story of the “Fall.” It holds up an ugly mirror for me, and for us all. One commentator I was listening to this week said he didn’t like calling this event the “Fall” because that makes it easier to let ourselves off the hook. We see it as a one-time event rather than as a story unfolding throughout time, that includes US, indeed is fundamentally about US.

He preferred to call this a story about our ongoing rebellion against God. THIS is the ugly mirror.

We are all Adam – following someone else’s actions without much thought, then blaming our behavior on that person.

We are all Eve – led astray by grand promises, without examining if they’re even feasible. And then again, blaming our behavior on someone else.

This story is a mess of ugliness. But it doesn’t start out that way.

Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann writes that in verses 15-17 a perfect order is set up by God. In verse 15 human beings are given work to do – a vocation – to “till” and “keep” the garden. In verse 16 we are given permit. God gives the man and woman permission to “freely eat.” And in verse 17 there is prohibition – the one thing they cannot do.

Brueggemann states, “These three verses together provide a remarkable statement of anthropology. Human beings before God are characterized by vocation, permission and prohibition…. Any two of them without the third is surely to pervert life.”¹

Our rebellion comes about when we think we can have a healthy relationship with God while neglecting any of the three.

Each of us is given a vocation in this life. It may not be our “job” necessarily – vocation is more than just what we do to make a living. Vocation is what we do with our life. How we go about operating in the world. The kind of person we are in and out of the specific jobs we’ve been given.

For Adam and Eve, their vocation was to “till,” to work the land, but it was also to “keep,” or care for it, which is more than simply plowing the fields.

And each of us is given tremendous freedom by God in our lives – permission. We are not puppets. God is not some puppeteer manipulating us like marionettes. The man and woman were permitted to eat from any tree in the garden, and free to “till” and “keep” the garden however they wanted.

And we all live with prohibition. There are certain things which are not good for us or for the community. We all need boundaries to keep us safe. We all know the prohibition faced by Adam and Eve. That’s where we almost always focus our attention – on what they could NOT do.

When we go against the grain of our vocation, when we abuse our freedom, when we neglect to follow boundaries – we find trouble – SIN.

That certainly happened for the man and the woman. Their rebellion against God’s prohibition caused disruption even in their freedom and vocation. Instead of following their vocation to “keep” the garden, they tore up plants to make coverings for themselves. Instead of enjoying their freedom, in verse 8 they’re hiding from God because of their nakedness.

What tempted them? We can never know Adam’s motives, but for Eve it was knowledge and power. “You will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

Those seem like good things to me, but the truth remains that the act crossed a boundary they were not allowed to cross. They had a relationship of trust and obedience with God, and now the trust and obedience were crushed.

Brueggemann writes, “They had wanted knowledge rather than trust. And now they have it. They now know more than they could have wanted to know. And there is no place to run.”²

Have you ever done something, and the second you’ve done it, you regret it? I know I have. And I can imagine that’s how Adam and Eve felt, but there was no going back.

Adam and Eve committed no “special” sin that caused God to send them out of the garden. Their sin was not unlike sin that you and I are tempted with every day. And like them, we lose. We act in ways that do NOT reflect God to whom we belong.

We betray our vocation as Christians every time we put someone or something before God, every time we pass by a person who needs help, every time we harbor negative thoughts about any race or class of person who God created.

God has given us permission to enjoy creation and our fellow creatures. But often we are just lazy. Not only that, we also abuse our freedom through our mistreatment of creation AND our fellow creatures.

And none of us like rules. Any kind of prohibition makes us bristle. We don’t like being told what we cannot do. Never mind that most of the time prohibitions are there for our safety and for the safety of others.

In the Ash Wednesday liturgy we are each invited to special repentance, fasting, prayer and works of love – the discipline of Lent. Today’s reading from Genesis invites us to see in Adam and Eve’s rebellion, our own rebellion.

Adam and Eve call us to reflect upon the ways in which we rebel against the vocation, permission and prohibition that characterize our relationship with God. And to repent. Not to point blame. But to stand naked before God and say, “I’m sorry. I confess.”

And then we experience a new and amazing freedom. A freedom so profound it defies words – but the closest word we have to describe it is – GRACE.

Amen.

¹Genesis. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Walter Brueggemann. John Knox Press, Atlanta; 1982, p. 46

²ibid, p. 49.

Some might balk at the idea that submissiveness is wrong. Of course God is always right! We should never challenge God! But Brueggemann gives many examples where the faithful have challenged God. The Psalms are filled with challenges to the way God has set things up. Brueggemann reminds us of Abraham and Moses speaking out or challenging God’s decision-making (Gen. 18:23ff and Exodus 32:1-14, 33:13-16, 34:8-9, Num. 11:10ff). “Conversations of serious engagement with God are not conversations in which God must always respond on our terms,” but that doesn’t mean they’re forbidden or that God doesn’t take them seriously (p. 60). It is CRUCIAL for us to bring our sufferings, our hurts, our pleas, our displeasure, our COMPLAINTS even about God

Some might balk at the idea that submissiveness is wrong. Of course God is always right! We should never challenge God! But Brueggemann gives many examples where the faithful have challenged God. The Psalms are filled with challenges to the way God has set things up. Brueggemann reminds us of Abraham and Moses speaking out or challenging God’s decision-making (Gen. 18:23ff and Exodus 32:1-14, 33:13-16, 34:8-9, Num. 11:10ff). “Conversations of serious engagement with God are not conversations in which God must always respond on our terms,” but that doesn’t mean they’re forbidden or that God doesn’t take them seriously (p. 60). It is CRUCIAL for us to bring our sufferings, our hurts, our pleas, our displeasure, our COMPLAINTS even about God